Scan barcode

A review by glenncolerussell

Zundel's Exit by Michael Hoffman, Markus Werner

Upon returning to his hometown of Zürich, Zündel reflects: "The city looks as though a million tongues are continually licking it clean. The people dress smartly, although some few affect a kind of casual chic. Their dialect is broad, their gait is bent and cramped, and I'm an old curmudgeon, now here's my tram."

Konrad Zündel is the central character of Zündel's Exit, Swiss author Markus Werner's first novel. Zündel is thirty-three, hardly qualifying as an old man but there's definitely something of Hermann Hesse's curmudgeon Harry Haller the Steppenwolf about him. And keeping to literary comparisons, Zündel's hypersensitivity and emotional topsy-turvy brings to mind the autobiographical novels of Karl Ove Knausgård.

Grouchy, emotional Zündel, a schoolteacher by profession, sets off on his own for summer vacation. Magda, his wife, will likewise be going her own way. From this splitting apart, we can infer the couple aren't exactly living a harmonious family life at the moment.

Zündel's Exit is an action packed page-turner compressed into a mere 115 pages. Ah, the misfortunes befalling Konrad the sad sack. Rather than delving into the arch of action (or, should I say, miscues), here's a list of Zündel call-outs preceding our hero's exit:

Zündel as youngish Steppenwolf - Like Harry Haller, Konrad swings back and forth - he cares about other people, society, history but wishes he didn't care a jolt; he denounces humanists, pacifists and utopians as whiners but he himself is a prime example of a sensitive heart who yearns for others to live an authentic life.

Zündel on affirming life - Konrad broods, "a hundred misfortunes aren't enough to rob a life-affirming fellow of his affirmativeness." Turning the pages, I was wondering if perhaps Konrad's affirming life is, in part, responsible for his naïveté, that is, projecting his own honesty onto others, even if those others are drug dealers, crooks, shady landlords. A piece of good news: there are those occasions when Konrad can focus his energy - on the heels of his ruminations regarding affirming life, he sits at his desk in his hotel room and writes from morning till midnight, after which he goes out for a walk and returns to write again until five the next morning.

Zündel'a backstory - Konrad's father Hans was a melancholy joker, sad dog and impulsive dreamer who couldn't stand anything resembling a well-mapped future. After getting a warm, pretty nurse by the name of Johanna pregnant, Hans takes off, destination unknown. Johanna is wild with pain and despair, slits her writs, is taken to an asylum and months later gives birth to Zündel. Fortunately, Johanna managed to raise Konrad with a love free of possession, not asking her son to provide support, emotional, financial or otherwise, denied her by the father of her child.

Zündel's dream - Midnight and Konrad wakes up bathing in sweat and shivering. He remembers a vivid dream: he's hanging on the face of a cliff. He spots a rescue helicopter hovering in front of him. Ah, he's saved! But then he recognizes the pilot at the controls: his father. His father eyes him calmly and veers away.

Zündel's follies - To list several: Konrad loses a tooth; he finds a human finger in a bathroom; in that same bathroom he discovers a wallet - his own, empty. Konrad believes a landlord who tells him Magda brought her brother up to their apartment (Magda has no brother); Konrad believes a drug dealer hands over a real pistol he, Konrad, paid good money for; Konrad is approached by a beautiful woman (such a handsome fellow!); Konrad goes to bed with a prostitute, Konrad returns to school in September and all hell breaks loose.

Zündel on men, women and ugliness - Konrad can hardly believe even if men are fat, misshapen or grotesque, they will not hesitate to pass aesthetic judgement on women. Yet when he's with a prostitute, he judges her only loveable trait is her ugliness since everything else about her strikes him as dead. Echoes of Nietzsche entering a house of prostitution (and, yes, in another section of the novel, Konrad makes reference to the great German philosopher).

Zündel on the news - At one point, Konrad rails: "A noun acquires a stiff adjective and sticks it to reality from behind. Endless, shameless, comfortless sentences and contents pair off, and the product of their unchastity is called a newspaper." Ultimately, Konrad seeks a raw, clean life beyond the superficiality and hypocrisy of words, words, words.

Zündel on the Swiss - Konrad asks what is the watchword of the Swiss - and then goes on to answer his own question: "Firstly, experience everything and risk nothing. Second: always be packed and ready." Reading this Markus Werner novel had me wondering how Zündel would have fared had he been raised in the United States. My suspicion is his judgement would have been at least equally harsh living in the land of commercialism, pop music and unending kitsch.

Zündel on humanity - "Humanity is assembled from partially reformed bed-wetters who never quite shake the feeling of existential displacement. No sphincter, no melancholy. Look at them, sipping their coffee." Ha! An aphorism worthy of Fritz. Like Nietzsche, Konrad is not at ease living in society; nay, even revolted at the prospect of finding his place among a species Aristotle termed "the social animal."

By my lights, Markus Werner carries on the spirit of Hermann Hesse with one major difference: in the end, unlike Hesse, he's no romantic - and that's understatement. I urge you to treat yourself to Zündel's Exit and discover for yourself the depth and splendor of this Swiss author's tale.

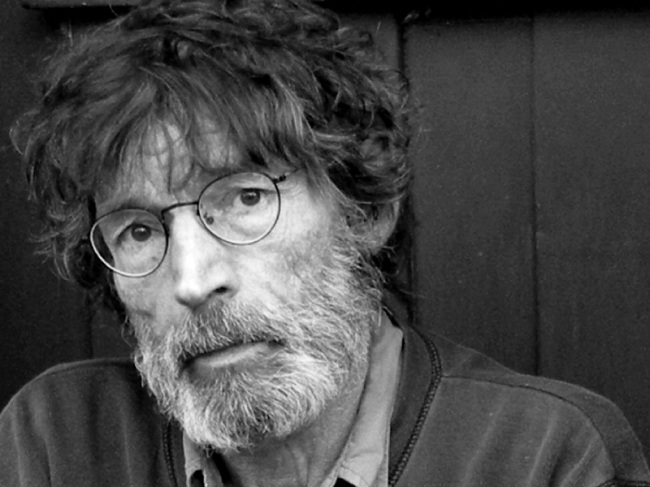

Swiss author Markus Werner, 1944-2016

"Zündel woke early the next morning in an almost peaceful mood. The feeling of finally confirmed unbelonging seemed as it were stripped of fear and defiance. It was this feeling, this one bright and radiant certainty, that he meant to cling to. And if in future some mendacious you're-not-really-so-very-all-alone-as-that blandishment should approach him, be it ever so pleasing, then he would not allow one iota of his belief to be charmed away." - Markus Werner, Zündel's Exit