Scan barcode

A review by glenncolerussell

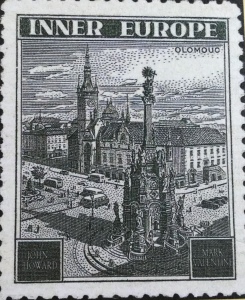

Inner Europe by Mark Valentine, John Howard

Inner Europe - Thirteen stories collected here, thirteen master strokes of the imagination complements of British authors John Howard and Mark Valentine.

We journey from Cornwall to the Dalmatian coast, from Iceland to lands bordering the Black Sea and many points between and beyond. John Howard's six stories and Mark Valentine's seven stories exemplify the book's dedication: To Europe: the beguiling, the enduring.

Oh, how John and Mark peel back the continent's outer skin so as to bend and morph European history in ways most uncanny. To share a taste of the authors' literary torquing, I'll focus on the following Inner Europe quartet:

THE ROSES OF RAVENNA by Mark Valentine

“The roses of Ravenna are fed by decay." The roses are “like little warning lamps, saying do not trespass upon this treacherous land, this salt terrain that still sends out its tongue towards the unreturning sea.” Taken from the story's first paragraph, words that foreshadow impending rot and degeneration since Ravenna roses serve not only as warning lamps but also irresistible lures for those unfortunates snared by their richly red spell.

The narrator reflects on the present state of the city and its environs where there are no more Byzantine vessels, gilded barges, gonfalons of merchant fleets. “Nor are the few human forms spared the desuetude that permeates this place.” But, yet, he remains a seeker of a true sovereignty, sanctity and beauty, most especially since he desires “to efface the memory of that image I saw which was – shall we say, the reverse of all those?" One may ask: exactly what image did the narrator see that he wishes to efface? Ah, one of Europe's ancient, mysterious, inner dimensions is disclosed but not until the tale's concluding paragraphs.

Chalk and paper in hand, it has been the narrator's practice to sketch the inhabitants of Ravenna, an artist forever on the lookout for facial signs bearing “the impress of the imperial, the mark of the most holy.” By a chance happening, he meets and then forms a keen friendship with an adolescent on the cusp of adulthood, a youth by the name of Casimir. "His hair was dusty gold, dishevelled always, his nose delicately flared like the opening of iris flowers, and his eyes - and this is always a sure sign - were that pale violet which is a last ray of the light of the imperial purple."

As he eventually learns, Casimir is a devotee of the god Nero and also third century boy-emperor Elagabalus, considered by many at the time to be the reincarnation of Nero. Elagabalus became known as Heliogabalus, as in The Roses of Heliogabalus, an 1888 painting depicting a royal banquet where the boy-emperor released a mountain of rose petals from a false ceiling, smothering unsuspecting guests.

In a barber shop (one of a number of echoes from Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice), our narrator also makes the acquaintance of an older, pasty skin Englishman with lucent blue eyes, one Lastingham, who turns out to be quite knowledgeable regarding ancient religions and cults. The narrator tells Lastingham about Casimir and his interests which leads to a dinner at Lastingham’s estate where the Englishman recounts for both Casimir and the narrator legends revolving around Heliogabalus, legends including the boy-emperor’s worship and identification with Syrian god Baal.

Weeks thereafter, the narrator begins hearing stories about Lastingham and Casimir having set forth on expeditions both east and west beyond Ravenna in quest of traces of an altar dedicated to Nero and/or the Syrian boy-emperor Elagabalus. What follows is a strange sequence of events bathed in the deep vermillion of Ravenna roses.

HERE IS MY COUNTRY by John Howard

“But no-one seems to remember the episode of the Graupen Library in Triberec. Nobody seems to be aware of it now, unless it is to recall what seems to be no more than a particularly odd dream. There is no-one except me-and one other.”

We're in Czechoslovakia in 1948, tumultuous times of shifting political power. The narrator informs us the Graupen Library is "a masterpiece of light and clarity,” the outer surface constructed of “sleek white concrete and lake-clear glass,” giving one the sense of spaciousness, a building designed by none other than the great Miles (Mies van der Rohe) famous for his International Style, a library funded by the family fortune of Franz Graupen, a man the town’s leading journalist, Marek Blažek, always referred to as the “Ultimate Connoisseur.” However, when some local hack politician’s plans insert themselves into the aforementioned shifting political power, miraculously, the Graupen Library has filled up with water.

A tale of the fabulous where the hard, brutal outer shell of European history can be so impenetrable, the Inner Europe of imagination and endless possibilities is sealed off, reduced to a strange dream, even if that dream is a collective dream documented by the contents of a library.

John Howard's tale bringing to mind multiple associations, among their number, Ray Bradbury's words: “You don't have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.” Yet, as we are in a Czechoslovakia invaded first by the Nazis then by the Soviets, for the narrator and Marek Blažek, beyond books and learning, there are deeper, more personal reasons to pound fist against heart and touch one's forehead before singing the Czech national anthem, "Czech land, home of mind, Czech land, home of mine."

THE FENCING MASK by Mark Valentine

Three teenage army deserters journey across the European countryside during a time of war. One evening, on the cusp of starvation, cautiously, very cautiously, the trio venture into an abandoned house. After gorging themselves on apples, they make their way along a passage to one of the last rooms where all is empty save for a chandelier holder on the ceiling in the form of a plaster satyr surrounded by carved grapes and two fencing masks hanging from a frayed golden cord. The narrator reckons the three of them are the first to have entered this room in years.

Thoroughly exhausted, they decide to sleep the night on the floor. With the first faint light of dawn, the narrator realizes one of the fencing masks is gone. In the far corner, he spots a figure that ought to have been Franz. “It wore his long black coat, like an old dandyish cloak. It had his worn boots. They were his pale hands fluttering about his head. But where his face should be there was only an oval of white and a black mesh.” He calls out but the mask does not reply; rather, the figure rises to its feet. “The right arm stretched out rigidly then flashed in a sequence of quick flourishes. The cloaked figure swirled, swerved, stepped aside, stood back, lunged.”

The narrator rouses Nico to watch the masked apparition fencing. All might seem like good sport and fun until “I seemed to hear a whistling in the air as though there were indeed a fine blade in my friend’s hand.” Is this a ghost story, a tale of psychic possession or one where the frenzied spirit of the pagan god Dionysus rears its satyr head to confront the three young deserters? A Valentine jewel rendered in the author's signature suavity.

SUN VOYAGER by John Howard

"Mr Lewis Bell came to Reykjavik because of the sculptures. So he told me at first, but that was only partly true. There was another reason." So begins this John Howard tale of desperation where Lewis Bell, an Englishman, travels to Iceland since he lost his life savings, his wife, everything. But as we read the final words of this compelling tale, we come to appreciate the magic of an Inner Europe offering transformation, both aesthetic and spiritual. True, it might take total desperation but the power of a work of art like Sun Voyager can provide nothing short of salvation.

Sun Voyager, created by Icelandic sculptor Jon Gunnar Arnason

John Howard

Mark Valentine